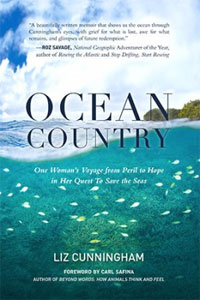

Last week I traveled to Fort Lauderdale to speak about Ocean Country at the Broward Library Foundation’s literary festival. Every year authors speak to high school students, mingle with guests at a large gala reception, and then each author is hosted at a separate dinner.

As I perused the advance schedule, I noticed my dinner was sponsored by the Friends of Birch State Park. A quick peek on Google Maps revealed an elongated patch of green—like a hidden gem—in the densely-developed grid of Fort Lauderdale. Too curious I called the Executive Director, Gale Butler.

“Could I come visit before the dinner?” I asked.

Fast-forward a few days and I was standing in the midday sun in front of a large house with a simple façade and clay-tile roof reminiscent of Provence. An athletic, graciously-dressed woman in her 60s was standing beside me—Gale Butler.

“This building was originally Hugh Taylor Birch’s home,” Butler said wistfully, “I remember riding horses in this park when I was a child.”

In the 1890’s Birch, a bearded man with a Darwin-esque physique, borrowed a sloop from a friend and sailed down the coast to South Florida. He fell so in love with it that he built a home there. As he neared death in the 1940s, witnessing the massive development boom, he bequeathed his land, 180 acres, to the state.

The gem of green—Birch State Park—was born.

“He was businessman and a naturalist.” Butler continued. “He was thinking about the future. He wanted people to remember what Florida used to be like. When you’re in the park, at moments you feel like you’re in the jungle.”

She wasn’t kidding.

Mark Foley, the Public Services Specialist, took me into the mangroves, 45 acres of them—a mix of white mangroves, which have light rounded leaves, and red mangroves with dark pointed leaves. In the afternoon light our canoe glided through narrow tunnels of leafy canopies. The contrasting reflections of light and dark colored leaves sparkled with disarming brilliance.

Foley, bearded and soft-spoken, pointed out each inhabitant with understated expertise. Tiny gray snail attached to a mangrove root? Periwinkle snail. Darting oval shapes at the bow of the canoe? Mullet. Flashes of gray wings? Tricolored herons. Yellow Crowned Night Herons.

“The other day,” Mark said with a contented yawn, “a mother manatee was here with her calf. At night on the full moon, you can see the bioluminescence.”

Preserving mangroves is no peripheral exercise. There are two main pathways to dealing with climate change. One: stop pumping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere. The other? Get carbon out of the atmosphere. Mangroves store fifty times more carbon in their soil per square meter than the same amount of Amazon rainforest.

Yes. Fifty times. They’re what’s called “blue carbon”—carbon stored in coastal and marine ecosystems, such as tidal marshes and sea grass beds.

Blue carbon is a lodestone of climate change mitigation. Add to that the fact that mangroves are nurseries for juvenile fish, stabilize coastlines and filter sediment from the water and well, they are seriously beautiful.

Afterwards Butler gave me a tour of the rest of the park with David Dearth, the Park Manager. With a broad smile, Dearth explained to me he’d served in the park service since 1997.

Everywhere we went—gopher tortoise habitat, waterfront, campground—Butler and Dearth overflowed with enthusiasm as they pointed each detail out.

“Yeah, the park’s great.” I thought, “But why this especially exuberant enthusiasm?”

Then it registered: they weren’t excited about maintaining the park, they were excited about restoring it. Non-native plants were being removed that had been choking a lake, plans were in place to make playgrounds accessible for the disabled and a new education center. The list went on.

The present moment has a power like no other—it’s our arena of action. But when it is framed by memory and wise vision for the future, that action acquires a salient agency. A cynic might say there’s no fixing the ills of our world, that we’re sliding towards inexorable catastrophe. Wisdom pulls out the ice-ax. The agency of the present moment—the response to the questions, What can we do? Who can we help?—that’s the golden fleece.

Certainly at moments the task of forging a sustainable future seems like an impenetrable challenge. More and more people mutter, “We’re toast! We’ve passed the point of no return!” But meeting this challenge doesn’t involve a new phenomena. It’s about doing something that we’ve been doing for thousands of years and which brings out the best in us. We just need to do it more: the age-old alchemy of action, courage, compassion and coming together as communities.

Hugh Taylor Birch had a memory of the wild coast he discovered, where marlin and swordfish weighing hundreds of pounds filled the waters and thousands of turtles laid their eggs on the beach. Without his wise action, Birch State Park wouldn’t exist, nor the three miles of public beach which gives Fort Lauderdale a beautiful waterfront and for many people, their livelihood.

A parallel process is happening now—a new cadre of people are working to ramp up restoration efforts and reinvigorate its capacity to inspire visitors. The Friends of Birch State Park is boosting that process through a capital campaign, a bench campaign, special events and volunteer opportunities.

Late in the afternoon Butler and Dearth and I walked beneath the canopy of Banyan tree that was over one hundred years old. Like stopping at a water fountain in a state of thirst, we lingered beneath the magnificent tree, drinking in the beauty. You couldn’t wrap your arms around the trunk of this tree. You’d need at least a dozen people holding hands to make that circle.

I took a photograph of Butler and Dearth beneath the tree. Their eyes were filled with joy and pride. It was a reminder that in the midst of a world in which many people feel overwhelmed by how much destruction is occurring, the task of restoration is not only vastly necessary, but offers a deep fulfillment that no other task can give.

To restore our earth we not only need to protect and restore remote places, but the small gems of nature in some of the most densely-populated parts of the world. And the people who do that—park rangers, volunteers, board members, donors—they too are the hidden gems of the world.

Near midnight after the fundraising dinner, Gale offered me a lift home. All the guests had left. She was the last to leave, locking the doors of Birch’s residence.

The road through the park had been lit by torches. “I’ll blow’em out,” I told Gale as she walked towards her car. “Pick me up near the entrance.”

The night air was warm and balmy. As I walked to the entrance, I zig-zagged across the road from torch to torch. With each torch I took a deep breath, sufficient to blow out the flames. When I blew the last one out, the road was shrouded in sweet darkness and the singing of crickets and cicadas. I paused and said a silent thank you to the man whose gift made that moment possible. Then two headlights appeared—Gale driving towards me.

To learn more about Birch State Park:

To learn more about blue carbon and climate change mitigation:

http://www.thebluecarboninitiative.org

Florida gopher tortoise photo courtesy of Craig ONeal, Wikimedia Commons

What a great experience! Thanks for sharing this. And as usual, you so eloquently mix the personal with the educational and a passionate plea for action. Bravo.